To create this application, we decided to follow our best practices for developing Shiny applications. These are the same practices we use and teach in our workshops.

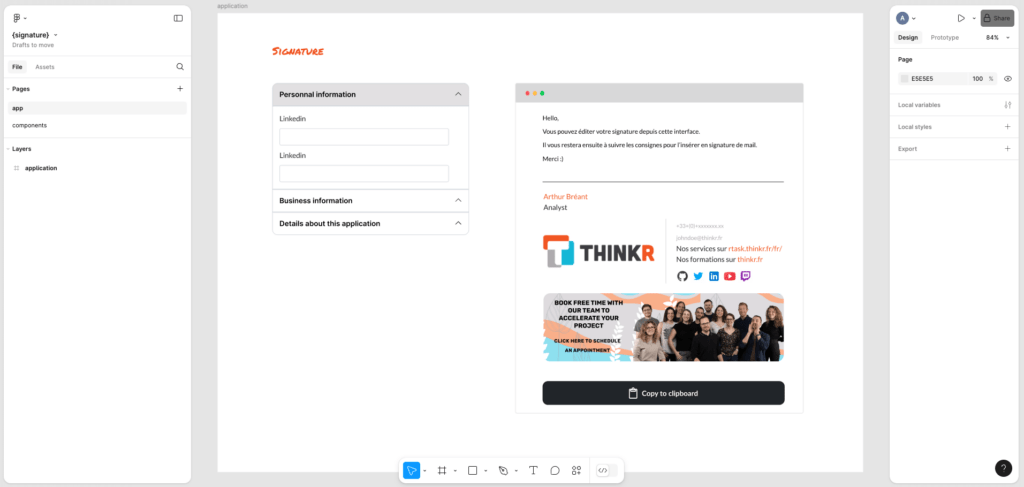

Creating a Mockup for the Application

We started by creating a mockup before coding the application. This allowed us to follow the different stages of mockup design:

Creating a low-fidelity (lo-fi) mockup followed by a high-fidelity (hi-fi) mockup.

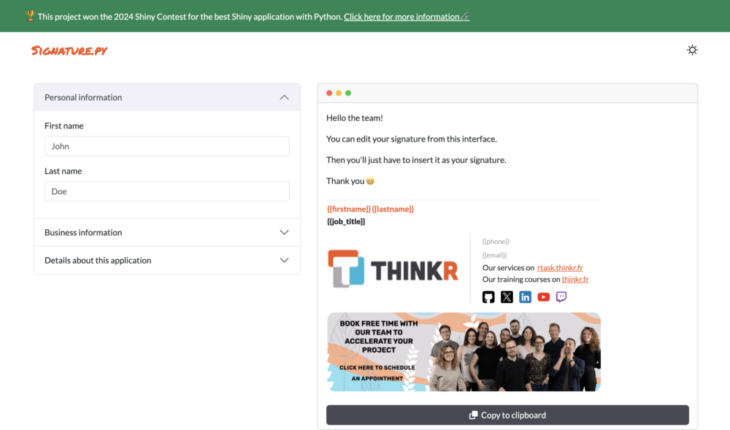

hi-fi mockup

We wrote a blog post (in French only) about the importance of mockups in application development. For this application, we followed the same process.

To build the mockup, we used state of the art tools, and the mockup can be accessed here.

Building the mockup before coding helps us: better understand the user’s needs (in this case, the ThinkR team) and better organize the application’s code.

Spending time on this step certainly helps save time during development.

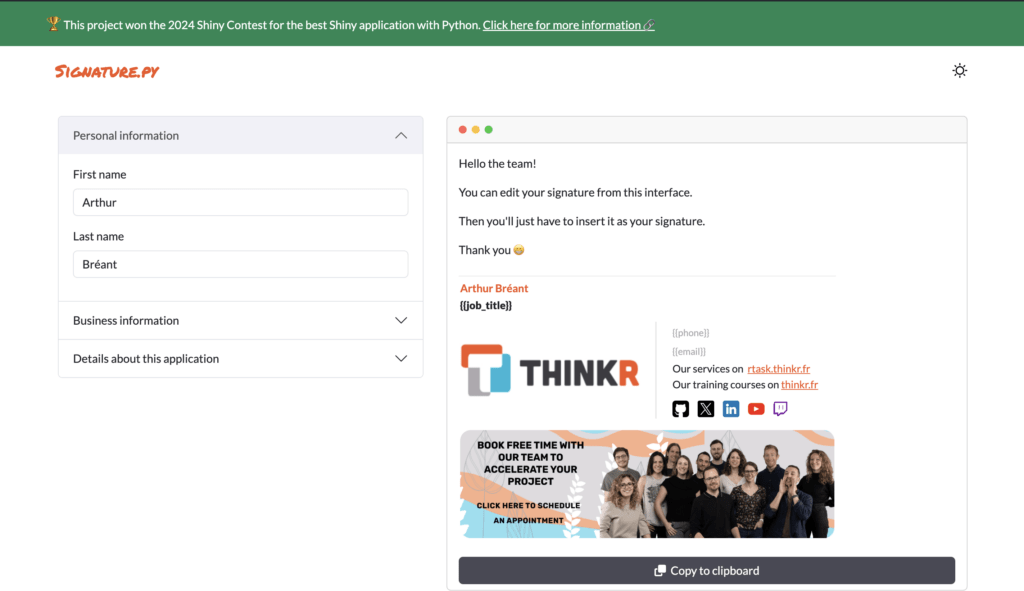

Building the Shiny Application with Python

For this application, we used the new {shiny} library for Python.

The full code of the application is available as open-source on our GitHub repository: ThinkR-open/signature.py.

Here’s an overview of the code structure:

Code Structure

The core of the application is located in the signature folder.

The app.py file is the main file of the application. It contains the application’s code.

Similar to our Shiny applications in R, the application is divided into two parts: the user interface and the server.

User interface

The user interface is defined in app_ui. The Python {shiny} library allows us to define the user interface using the ui class, which generates the various UI elements.

app_ui = ui.div(

ui.div(

ui.page_fixed(

ui.head_content(

ui.tags.title("signature.py"),

ui.include_css(current_dir / "css" / "signature.css"),

ui.include_js(current_dir / "js" / "signature.js"),

mod_navbar.navbar_ui("nav_signature"),

ui.div(

ui.div(

mod_form.form_ui("form_signature"),

mod_preview.preview_ui("preview_signature"),

class_="row",

),

class_="container",

),

),

)

Just like Shiny applications in R, it’s possible to divide the application into several modules. This helps organize the code and makes it more readable.

Thus, the modules folder contains the different modules of the application. Each module is a file consisting of two functions: one for the user interface and one for the server.

Server

On the server side, the application is defined in app_server. The Python {shiny} library defines the server using the server function.

Just like in R, we can also use the small-r strategy in Python.

def server(input: Inputs, output: Outputs, session: Session):

reactive_values = reactive.Value(

{

"firstname",

"lastname",

"jobtitle",

"email",

"email_url",

"phone",

"phone_url",

}

)

mod_form.form_server("form_signature", reactive_values=reactive_values)

mod_preview.preview_server(

"preview_signature", current_dir=current_dir, reactive_values=reactive_values

)

Styling the Application

Here, nothing changes between R and Python. Shiny still natively includes the Bootstrap CSS library.

Thus, we can use the classes provided by Bootstrap to style the application.

app_ui = ui.div(

ui.div(

ui.div(

ui.span("🏆 ", class_="fs-5"),

ui.span(

"This project won the 2024 Shiny Contest for the best Shiny application with Python. ",

class_="fs-6",

),

ui.a(

"Click here for more information 🔗 ",

href="https://posit.co/blog/winners-of-the-2024-shiny-contest/",

target="_blank",

class_="text-white",

),

class_="container",

),

class_="sticky-top bg-success text-white p-3",

)

)

This snippet of code adds a green banner at the top of the application, with a sticky position that stays at the top of the page even when scrolling. The banner also has some padding and white text color.

We adapted the application’s colors to match the ThinkR brand in the scss folder and the signature.scss file.

In this file, colors are defined as Sass variables, which are reused throughout the stylesheet:

$primary: #b8b8dc;

$secondary: #f15522;

$info: #494955;

$close: #ff5f57;

$minimize: #febc2e;

$zoom: #27c840;

.navbar {

padding: 1.5em 0;

.navbar-brand {

font-size: 1.5em;

font-family: "Permanent Marker", cursive;

pointer-events: none;

color: $secondary;

}

}

Copying the Email Signature

To copy the email signature, we used an external JavaScript library: {clipboard}. This library allows us to copy text to the clipboard.

$(document).ready(function () {

$("#preview_signature-copy").click(function () {

new Clipboard("#preview_signature-copy");

});

});

To ensure this file is included in the application, just like the CSS file, we need to include the JS in the UI:

ui.include_css(current_dir / "css" / "signature.css") ui.include_js(current_dir / "js" / "signature.js")

Signature Template

To generate the signature, we used an HTML template. This template is stored in the template folder in the template.html file.

In R, this would be equivalent to using the htmlTemplate function from {shiny}.

Well documented in R, this feature is currently missing from the Python{shiny} documentation.

However, here’s how signature.py uses the HTML template:

The preview of the signature is generated from the HTML template. The template is read, and the values are replaced by the ones entered in the app’s reactive value reactive_values. This reactive value is initialized in app.py and passed to the modules mod_form and mod_preview.

reactive_values = reactive.Value(

{

"firstname",

"lastname",

"jobtitle",

"email",

"email_url",

"phone",

"phone_url",

}

)

As the user fills in the form, the reactive value is updated.

@module.server

def form_server(input: Inputs, output: Outputs, session: Session, reactive_values):

@reactive.effect

@reactive.event(

input.firstname, input.lastname, input.job_title, input.email, input.phone

)

def _():

reactive_values.set(

{

"firstname": input.firstname(),

"lastname": input.lastname(),

"job_title": input.job_title(),

"email": input.email(),

"email_url": f"mailto:{input.email()}",

"phone": input.phone(),

"phone_url": f"tel:{input.phone()}",

}

)

Finally, the template is read, and the values are replaced by the entered values. To do this, we use the Python {jinja2} library. We fetch the template and the entered values, then pass them to the template.

The template is then rendered in the application.

def preview_server(

input: Inputs, output: Outputs, session: Session, current_dir, reactive_values

):

env = Environment(loader=FileSystemLoader(current_dir))

template = env.get_template("template/template.html")

@render.text

def render_template() -> str:

print(reactive_values())

first_name = reactive_values().get("firstname")

last_name = reactive_values().get("lastname")

job_title = reactive_values().get("job_title")

email = reactive_values().get("email")

email_url = reactive_values().get("email_url")

phone = reactive_values().get("phone")

phone_url = reactive_values().get("phone_url")

rendered_template = template.render(

firstname="{{firstname}}" if first_name == "" else first_name,

lastname="{{lastname}}" if last_name == "" else last_name,

job_title="{{job_title}}" if job_title == "" else job_title,

email="{{email}}" if email == "" else email,

phone="{{phone}}" if phone == "" else phone,

email_url="{{email_url}}" if email_url == "" else email_url,

phone_url="{{phone_url}}" if phone_url == "" else phone_url,

)

return rendered_template

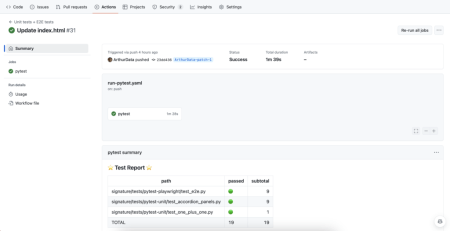

Tests

We continue to follow the best development practices that we know in R and reuse them in Python. We used the {pytest} library to write unit tests.

The tests are stored in the tests/pytest-unit folder, with the files test_accordion_panels.py, test_one_plus_one.py (got to start somewhere).

Here, we are performing unit tests. This means we focus on testing a specific function or module. The goal is to test the behavior of a function rather than the behavior of the entire application. These tests are primarily business/domain-related tests.

A Python test looks like this:

def test_one_plus_one():

assert 1 + 1 == 2

In parallel, we also wrote End-to-End (E2E) tests. These tests allow us to test the entire application. They help ensure that the application works correctly as a whole. The objective here is to simulate user behavior. To do this, we use the {playwright} library, which allows us to simulate user interactions.

These tests ensure that the application works correctly as a whole by testing the integration of different modules. Unlike unit tests, which focus on isolated functions or components, E2E tests simulate a complete user scenario. For example, they can verify that filling out a form properly updates the data and generates a correct signature. This helps detect errors that might arise during interactions between modules, thus enhancing the overall reliability and user experience of the application.

E2E tests are stored in the tests/pytest-playwright folder, in the file test_e2e.py.

An E2E test in Python looks like this:

from shiny.run import ShinyAppProc

from playwright.sync_api import Page, expect

from shiny.pytest import create_app_fixture

app = create_app_fixture("../../app.py")

def test_signature(page: Page, app: ShinyAppProc):

page.goto(app.url)

response = page.request.get(app.url)

expect(response).to_be_ok()

expect(page).to_have_title("signature.py")

Continuous Integration

All the way through, we adhere to best development practices. We also set up a continuous integration pipeline for this application.

The continuous integration pipeline is stored in the .github/workflows/run-pytest.yaml file. This file contains the different steps of the pipeline.

Each time a push is made to the GitHub repository, the pipeline is triggered. It runs the unit tests and the E2E tests. If the tests pass, the pipeline turns green. If not, it turns red.

name: Unit tests + E2E tests

jobs:

pytest:

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

steps:

...

- name: 🧪 Run tests

run: poetry run pytest --github-report -vvv --browser webkit --browser chromium --browser firefox

This is a great way to ensure that the application works correctly before deploying it to production. Here, the application is tested on three browsers: Webkit, Chromium, and Firefox.

Updating the Banner Imager

To update the banner image, simply update the image in the GitHub repository. The image is stored in the signature/assets folder, in the file current_banner.png.

Once the image is updated, it will directly impact the application and all the signatures generated with the app.

Deploying the Application on Our Servers

This application is deployed on our servers. You can view it online: signature.py.

This Python application lives alongside our other R applications on our servers. Feel free to contact us if you want to deploy your Python or R applications to production.