So, some months ago, I spent a few hours over a few days puzzled by something that turned out to be straighforwardly written up in the Stata manual, but not easily findable anywhere else. So I want to write it up, if only to have somewhere for future me to find it easily.

It’s all about the design effect in a complex survey. The definition of a design effect given by Wikipedia is fine:

“In survey methodology, the design effect … is a measure of the expected impact of a sampling design on the variance of an estimator for some parameter of a population. It is calculated as the ratio of the variance of an estimator based on a sample from an (often) complex sampling design, to the variance of an alternative estimator based on a simple random sample (SRS) of the same number of elements.”

So a design effect of 1 means the variance of your estimator (and hence its standard error) is the same in your complex survey design as if you’d just sampled simply from the population at random. Values higher than 1 are the norm, and mean that you have a higher variance in your estimate as a price of something else in your complex design (for example, maybe you are sampling clusters that live closer together to make it easier for interviewers to interview several households at once, which reduces cost but increases variance).

My puzzle related to when you are estimating some measure of interest over different levels of a categorical variable that features in the sample design (say, the unemployment rate in different states of Australia, in a survey where the sample was stratified by state), and in particular when some levels been over-sampled and some under-sampled. By which I mean, the fraction of the total population that has been sampled is different for different levels of this variable. Perhaps Tasmania (a small state) was over-sampled from to make sure there were enough people to report on unemployment separately for Tasmania.

A concrete example I’m going to use is a survey that was stratified by province, and some provinces have had a high proportion of the population sampled for some reason that we don’t need to worry about, but let’s presume it’s a good one (like, wanting a minimum number of people from each province to report the estimate of interest with a reasonably small confidence interval). The variable of interest in this survey is likes_cats which is either 1 or 0 and indicates whether the survey respondent likes cats. (Warning – no attempt has been made to make the proportion who likes cats in this made up data resemble reality).

The thing that started me on this as a problem was noticing differences between Stata and R output, so I’ll be structuring the blog around that. I guess this also serves the useful case of an example of the same survey being analysed in both environments.

The data I’m using is made up, but based on real life data that I’ve mangled, re-simulated, and generally fiddled with to avoid any privacy questions. Let’s start by downloading it, importing it to R, and specifying the survey design using Thomas Lumley’s survey package.

library(tidyverse)

library(scales)

library(survey)

url <- "https://raw.githubusercontent.com/ellisp/blog-source/refs/heads/master/_working/simulated-survey.csv"

df <- "simulated-survey.csv"

if(!file.exists(df)){

download.file(url, destfile = df)

}

sim_surv <- read_csv(df)

# Specify survey design - stratified by province, and 2 stages, both with finite populations

sim_surv_des <- svydesign(~neighborhood + ind_id, weights = ~fweight,

strata = ~province,

fpc = ~nb_in_province + pop_in_neighborhood,

data = sim_surv, nest = TRUE)

And here’s doing the same in Stata, other than the downloading part given we’ve already done that once:

** Simple Stata demo of survey design and calcualtion, assumes data has been

** previously downloaded in the accompanying R script

clear

import delimited simulated-survey.csv

** make a numeric version of province, as over() can't work with strings:

encode province, gen(province_n)

** Set up survey design = complex 2 stages design stratified sample

** first step of sampling design is selection of neighborhoods from each province with finite neighborhoods,

** second step is individuals select from the finite population in each neighborhood

svyset neighborhood [pweight=fweight], singleunit(centered) ///

strata(province) fpc(nb_in_province) || ind_id, fpc(pop_in_neighborhood)

These are pretty similar workflows. Stata has the extra step – for Reasons – of encoding a string variable we’re going to want to use later as numeric. R’s svydesign function and the Stata svyset function do essentially identical jobs in a pretty similar way, telling the software the stratified, two stage design we’re going to be using and giving it the columns to look at for the finite population corrections. Our sample design is to pick a number of neighbourhoods in each province, and then a number of individuals in each neighbourhood, so we’re interested in both the total number of neighbourhoods in each province and the total number of individuals in each neighbourhood.

(Note – in real life I would be declaring that the sun of fweight in each province has been calibrated to match the population total in that province, but doing this introduced some further limitations with Stata that I decided were distractions, to look at some other time.)

To check that we’re in agreement, let’s start by asking both environments the proportion of people that like cats, the standard error of that proportion, and the design effect.

In R:

> svymean(~likes_cats, design = sim_surv_des, deff = TRUE)

mean SE DEff

likes_cats 0.5320009 0.0065751 1.8673

And in Stata:

. ** Population level design effects

. svy: mean likes_cats

. estat effect

----------------------------------------------------------

| Linearized

| Mean Std. Err. DEFF DEFT

-------------+--------------------------------------------

likes_cats | .5320009 .0065751 1.86726 1.31766

----------------------------------------------------------

Note: Weights must represent population totals for deff to

be correct when using an FPC; however, deft is

invariant to the scale of weights.

(Some of Stata’s output has been edited out)

OK, so we see that both systems agree that 0.5320009 of people like cats, that the standard error for this is 0.0065751, and the design effect is 1.86726.

So far so good, but what we are interested in is what proportion of people in each province like cats. Here is what R has to say about this:

> svyby(~likes_cats, by = ~province, design = sim_surv_des, FUN = svymean, deff = TRUE)

province likes_cats se DEff.likes_cats

A A 0.6657223 0.01910098 1.676309

B B 0.6345405 0.01423610 1.257485

C C 0.6096537 0.02125743 2.050192

D D 0.5706099 0.02251630 2.852858

E E 0.4392845 0.01633982 1.748840

F F 0.6783198 0.01831859 2.103528

G G 0.4153480 0.01535588 1.217967

H H 0.4066567 0.01329190 1.258354

…and here is Stata:

. ** Strata level design effects

. svy: mean likes_cats, over(province_n)

. estat effect

----------------------------------------------------------

| Linearized

Over | Mean Std. Err. DEFF DEFT

-------------+--------------------------------------------

likes_cats |

A | .6657223 .019101 .637551 .769941

B | .6345405 .0142361 1.3455 1.11852

C | .6096537 .0212574 2.31479 1.46709

D | .5706099 .0225163 3.13267 1.7067

E | .4392845 .0163398 2.01139 1.36757

F | .6783198 .0183186 1.895 1.32741

G | .415348 .0153559 .597809 .745558

H | .4066567 .0132919 1.74908 1.27528

----------------------------------------------------------

This time the point estimates and the standard errors are different, but the design effects are radically different. For example, in province A, R gives a design effect of 1.68 (meaning that the variance of the estimate is 68% bigger as a result of the complex survey sampling design), but Stata gives 0.64 (meaning the variance of the estimate is 36% lower because of the design).

Why is this so? In particular, how can the design effects be different, when the estimated standard errors are identical?

Well, the answer turns out to be pretty straightforward. In the Stata manual for estat effect it says we have an option srssubpop which will “report design effects, assuming simple random sampling within subpopulation” (emphasis added) and:

…by default, DEFF and DEFT are computed using an estimate of the SRS variance for sampling from the entire population.

As per Wikipedia, the design effect is a comparison of the actual estimated standard error of the proportion of people who like cats in each province, with the standard error “you would have got with a simple random sampling design” (it is actually the ratio of the variances, which is the squared standard error, but as we are typically thinking in terms of standard error and that is what both R and Stata return, I’m emphasising that part of the concet).

But there are two ways of looking at this variance that “you would have got with a simple random sampling design”.

One way is to say that you have the sample numbers in each province that you have, but let’s pretend the design that gave it to you was just simple random sampling, and calculate the standard error accordingly; square both standard errors and divide one by the other. This is what is happening in R.

The other ways is to reflect on one more step, and say “hang on, if we’d really had a simple random sample, we wouldn’t have these sample sizes in the first place. For example, we’ve only got 864 samples in province A because we deliberately oversampled there. If we’d used simple random sampling, it would have been more like 362. Let’s compare our standard errors from the actual sample to the standard errors we would have likely got from simple random sampling, including less people in province A and more in province G than we actually got.” This is what is happening in Stata. That’s why province A has that design effect of 0.64 – the stratified sample design gave us extra samples in province A, so the design is actually giving us reduced variance there, compared to a genuine simple random sample.

So the reason this second method has a design effect of less than 1 for province A is that it says “the only reason you have so many people in your sample from province A is the stratification part of the sampling design. So when we want to say ‘what impact has the design had on our estimates’, it’s only fair to say that the estimate you’ve got is a lot more precise than you would have under simple random sampling.”

I actually find this a pretty intutitive interpretation, if we want to use the design effect as a short hand for “what impact has our design had on this particular estimate’s variance”. Of course a lot of this is largely academic; design effects are only really worried about by specialists, and they are often focused on as a single number for the survey as a whole (focusing on the impact of the design on the key variable of interest, estimated for the whole population), which doesn’t vary by either method. And the two methods of getting design effect will only vary much when, like in our case, the categorical variable you are splicing your sample up into for estimation purposes happens to be the very variable that you used as a basis for over- and under-sampling in the first place.

Stata conveniently gives you an easy option to use the alternative method of calculating a design effect, just adding the , srssubpop option to the estat effect command:

. estat effect, srssubpop

----------------------------------------------------------

| Linearized

Over | Mean Std. Err. DEFF DEFT

-------------+--------------------------------------------

likes_cats |

A | .6657223 .019101 1.67631 1.18258

B | .6345405 .0142361 1.25748 1.08378

C | .6096537 .0212574 2.05019 1.38623

D | .5706099 .0225163 2.85286 1.63379

E | .4392845 .0163398 1.74884 1.28105

F | .6783198 .0183186 2.10353 1.39313

G | .415348 .0153559 1.21797 1.02739

H | .4066567 .0132919 1.25835 1.09248

----------------------------------------------------------

We see these design effects exactly match those from R, eg the design effect for province A is now 1.676.

Here’s what the Stata manual says about which method to choose:

“Typically, srssubpop is used when computing subpopulation estimates by strata or by groups of strata.”

This is a little terse but I presume the logic here is that if you stratified your sample, perhaps you want to compare to simple random sampling within those strata – not to from the population as a whole. In otherwords, you’re not really comparing your complex survey design to the simples of all simple random sampling, but to stratified random sampling.

The survey package in R defaults to the equivalent of Stata’s srssubpop option. As far as I could tell, R doesn’t give an equivalently easy way to get the design effects that Stata defaults to. But they aren’t hard to calculate yourself. The table below is meant to be a step-by-step guide to how this was done:

avg_weightis the average individual weight of sample units in each province. Lower weights mean that each sampled person represents less of the total population than is the case for heigher weights.pis the estimated proportion of people in that province that like cats, calculated straight from the datanis the actual sample sizeNis the population size in that provinceeven_nis the hypothetical approximate sample size you would have drawn from that population under simple random samplingse_with_actual_nis the standard error, pretending there is no complex survey design to worry about, with the actual number of samples in that province. In other wordssqrt(p * (1 - p) / n * (N - n) / (N - 1))which is the usual standard error for a proportion, with finite population correction.se_with_even_nis the same but calculated with the hypothetical more even sample size if you’d hard real simple random sampling. So same as the above, but usingeven_ninstead ofn.se_complexis the actual standard error, taking into account the complex survey design.DEff_1is(se_complex / se_with_even_n) ^ 2ie the Stata default methodDEff_2is(se_complex / se_with_actual_n) ^ 2ie the R default method

| province | avg_weight | p | n | N | even_n | se_with_actual_n | se_with_even_n | se_complex | DEff_1 | DEff_2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 6.033866 | 0.6657223 | 854 | 5152.921 | 362 | 0.0147457 | 0.0239095 | 0.0191010 | 0.6382190 | 1.677948 |

| B | 15.167991 | 0.6345405 | 1345 | 20400.948 | 1432 | 0.0126908 | 0.0122711 | 0.0142361 | 1.3458988 | 1.258358 |

| C | 15.946476 | 0.6096537 | 1013 | 16153.780 | 1134 | 0.0148393 | 0.0139691 | 0.0212574 | 2.3157141 | 2.052091 |

| D | 15.539426 | 0.5706099 | 1291 | 20061.399 | 1408 | 0.0133260 | 0.0127205 | 0.0225163 | 3.1331916 | 2.854927 |

| E | 16.230320 | 0.4392845 | 1515 | 24588.934 | 1726 | 0.0123520 | 0.0115194 | 0.0163398 | 2.0120421 | 1.749924 |

| F | 12.927955 | 0.6783198 | 1263 | 16328.008 | 1146 | 0.0126258 | 0.0133060 | 0.0183186 | 1.8953402 | 2.105066 |

| G | 7.497966 | 0.4153480 | 1088 | 8157.787 | 572 | 0.0139086 | 0.0198700 | 0.0153559 | 0.5972474 | 1.218938 |

| H | 19.407325 | 0.4066567 | 1631 | 31653.346 | 2221 | 0.0118457 | 0.0100508 | 0.0132919 | 1.7489189 | 1.259086 |

For variables not highly correlated with the over/under-sampling structure, the design effects will not vary by much the two methods. For variables that are, the Stata manual suggests using the srssubpop. What this suggests to me is that it is safe to use the srssubpop option more generally – when it makes much difference is precisely the time that it is more likely to be used.

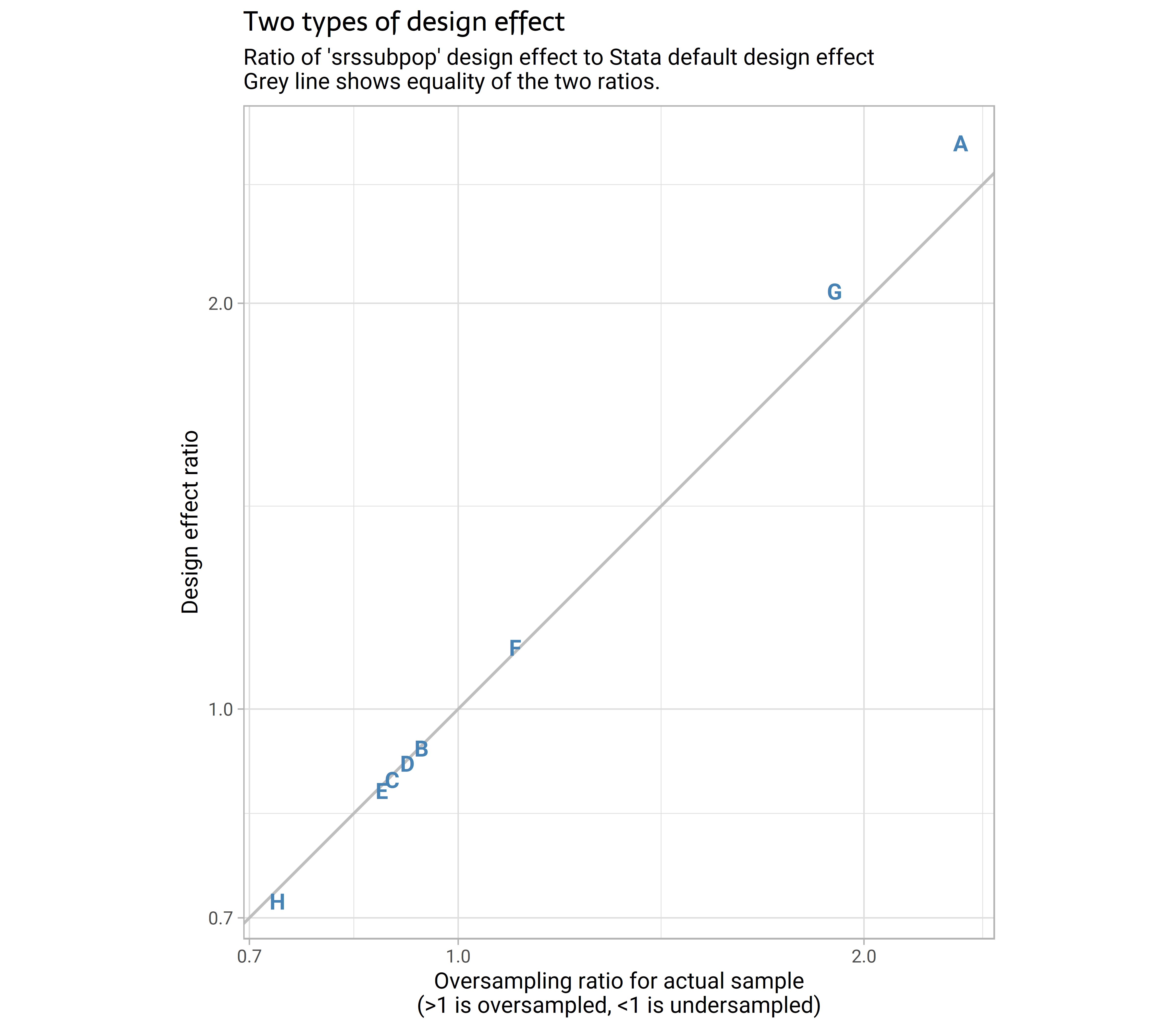

I (literally) can’t have a blog post without a plot, so here is an attempt to show some of the key information from that table visually. I tried a few different ways to show this visually, and ultimately opted for just comparing two ratios – that of the design effect from one method compared to the other, and the actual sample size compared to the expected sample size under unstratified simple random sampling.

Here’s the code that calculated that table and drew the plot:

results <- sim_surv |>

group_by(province) |>

summarise(avg_weight = mean(fweight),

p = weighted.mean(likes_cats, w = fweight),

n = n(),

N = sum(fweight)) |>

ungroup() |>

mutate(even_n = round(N / sum(N) * sum(n)),

se_with_actual_n = sqrt(p * (1-p ) / n * (N - n) / (N - 1)),

se_with_even_n = sqrt(p * (1-p ) / even_n * (N - even_n) / (N - 1)),

se_complex = svyby(~likes_cats, by = ~province, design = sim_surv_des, deff = TRUE, FUN = svymean)$se,

DEff_1 = (se_complex / se_with_even_n) ^ 2,

DEff_2 = (se_complex / se_with_actual_n) ^ 2)

results |>

mutate(ratio_n = n / even_n,

ratio_deff = DEff_2 / DEff_1) |>

ggplot(aes(x = ratio_n, y = ratio_deff, label = province)) +

geom_abline(slope =1 , intercept = 0, colour = "grey") +

geom_text(colour = "steelblue", fontface = "bold") +

scale_x_log10() +

scale_y_log10() +

labs(x = "Oversampling ratio for actual sample\n(>1 is oversampled, <1 is undersampled)",

y = "Design effect ratio",

subtitle = "Ratio of 'srssubpop' design effect to Stata default design effect

Grey line shows equality of the two ratios.",

title = "Two types of design effect") +

coord_equal()

Cheerio.

Related