The creation of a common language to store and query data for the aerospace and defense (A&D) industry is underway, with original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) like Airbus and Boeing set to benefit from widely recognized and accepted terms for parts and operations.

In late January, Thomas Barré, Solution Architect at Airbus, gave a lecture and answered questions about The Common Language project that he initially developed for internal use at Airbus. He shared this information in a webinar hosted and moderated by James Roche, A&D practice director for CIMdata, an Atlanta-based global strategic management consulting and research company focused on Product Lifecycle Management (PLM).

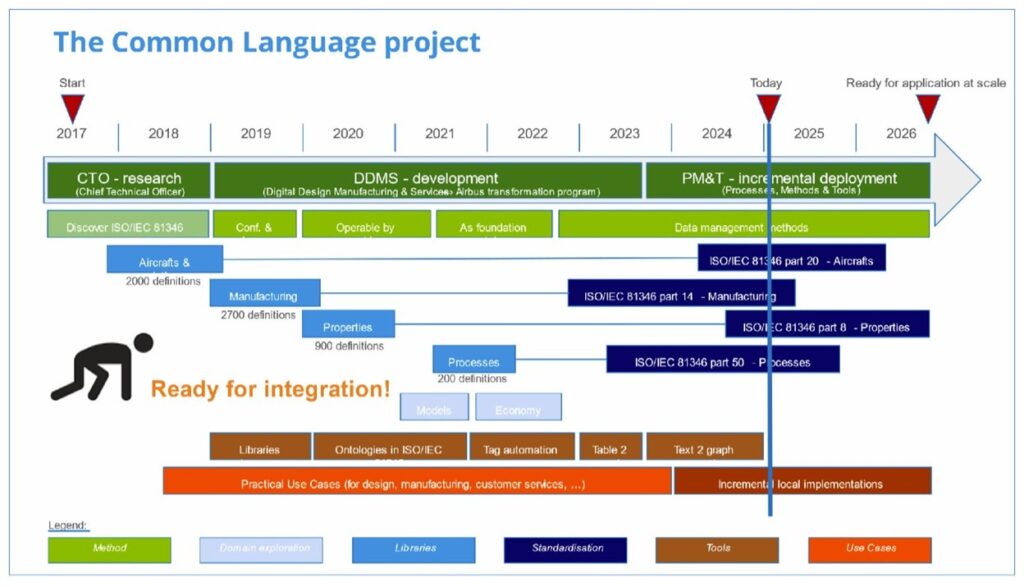

Barré said that by mid-2026, The Common Language project is expected to be ready for application at scale. The language will offer OEMs beyond A&D with easy paths for people and machines to clarify, federate and pose questions to blocks of data.

“Prior to the development of this common language, OEMs have spent tens of thousands of hours searching for data without a Rosetta stone to navigate terminology and definitions. Point-to-point mapping across hundreds of IT applications must be updated each time

an application is added or modified. The [way] to overcome this obstacle is to create a standard—which is a consensus by nature—with key players of the domain. [This is] then available for application within aircraft programs as needed,” say Barré and Roche.

The language is built on International Organization for Standardization/International Electrotechnical Commission (ISO/IEC) 81346, a series of international standards originally developed for construction projects like buildings.

A next step for supporters of the language could be finishing the introduction of the knowledge created by Airbus into the ISO/IEC 81346 series and potentially Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) standards, with support from experts of the domains. Additional steps could include expanding the recognition of the standard to other standardization bodies and continuing to promote the language. Adopters and developers could work to set up internal and collaborative use cases of the language. With the support of the authors of the standard, Airbus has already developed extensions for additional domains, including energy transformation plants, manufacturing, processes, aircraft and properties.

How the language works and solutions for legacy systems

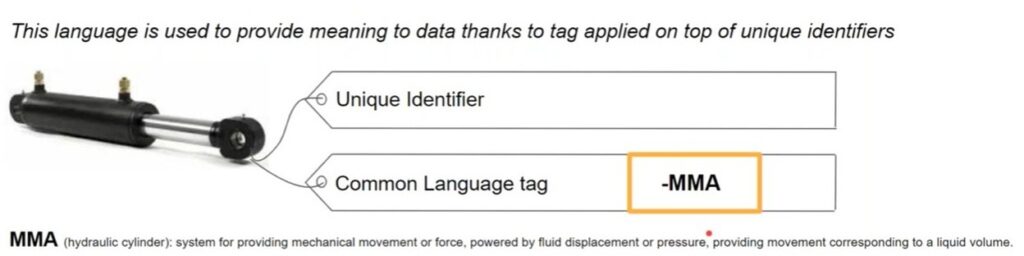

The key action necessary to create the language is the attachment of a common language tag for definition to an object or process. For example, the tag “MMA” would be attached to a hydraulic cylinder. An OEM would not be required to rename the part.

An OEM should clearly differentiate between the tag and the elements that provide meaning about the object. Tags should not carry any meaning. Tags are stable over time and serve only to distinguish one object from another. This allows OEMs to continue using their own naming conventions for data and files. Currently, each actor in the aerospace industry has different naming and modeling policies.

“It would be utopia to move to a single naming and modeling convention. It is acknowledged (this) may be unrealistic,” say Roche and Cheryl Peck, chief marketing officer for CIMdata.

By connecting data to a shared definition through the common language, the system can retrieve related information from different parties. This enables each actor to maintain their own naming and modeling conventions. This approach simplifies data management, promotes access and eases integration between OEMs and their supply chain.

According to Roche and Peck, the best way to promote the new language is to create a pilot project by using an existing project in which data is already being shared. Alternatively, an OEM could create the pilot program by shadowing the current data exchange methods to demonstrate the language’s performance. If there is no current project, the OEM could develop a new test project to apply the common language principles and showcase the benefits for interoperability.

Infrastructure for implementation and the standard for digital twins

An OEM using the common language should create a reference model that uniquely identifies each element without modifying its existing legacy system. An important step will be to distinguish between conceptual elements and their specific instances. For example, the idea of a bolt versus individual bolts used in operations.

A structured approach should simplify a user’s navigation of data and reduce complexity. The model offers flexibility and acts as a universal framework. An OEM should carefully consider implementation details. Legacy systems and new processes need to coexist.

Another ISO standard, ISO 23247, is applicable to digital twins. The latter is defined as digital models of a physical product, simulation or process. This ISO standard provides some guidance on naming and identifying a subject’s numerical twin. An OEM could merge the two approaches because ISO 81346 and ISO 23247 are fully complementary.

“ISO 81346 provides a language of concepts and definitions, acting as a dictionary and

grammar to describe a system. ISO 23247 serves as a framework for digital twins in the industrial sector, helping create specific models of industrial systems for various purposes,” say Roche and Peck.

They say an OEM should use the common language from ISO 81346 to describe the

elements within the models defined by ISO 23247. ISO 23247 specifies the key information to be included in a digital twin, while ISO 81346 ensures that each item within the model is described unambiguously.

The common language can be applied across industries because it provides a solid foundation for broader adoption.

“Organizations in any domain are encouraged to use this approach to enhance cross-industry understanding and interoperability,” says Roche and Peck.

Other requirements to work with the language

Through his last seven years of work developing and promoting the common language, Barré says the ability to label items required four elements: a standard for naming items that was based on characteristics of that item, a protocol to attach a label to an item based on characteristics of the item; a means to extract those characteristics from sources in multiple formats, including tables and free form text; and automation of the process for labeling billions of items with a practical level of effort and in a practical timeframe. These elements helped the labeling proceed efficiently and on a massive scale without disruption to a business. Barré also developed Artificial Intelligence (AI) tools for automated labeling.

Barré is now freely offering the four methods and tools that he developed to peers. OEMs interested in The Common Language project can test the language for their own applications and/or participate in the standardization of the language by sending an email to [email protected].

One of the most significant statements that Barré made in the January webinar was, “Data is the new gold.” He added OEMs that can manage and utilize data about parts and processes will be ahead of their peers. They will be able to retrieve any needed information from billions of data.

Brian Pickett, Digital Transformation Leader at Spirit AeroSystems, which is a tier one aerospace supplier, said Barre’s discussion helped him see the positive side of a data silo. The term refers to a set of data controlled by one department within an organization, like a company’s IT department.

“When I think of a data silo, I think of something bad. It’s just cored up and locked up. This (the common language) is a framework, as I see it, for effective use and management of that data,” said Pickett.